Complete this sentence: “If you get bucked off the horse…”

“Get back on,” right? “If you get bucked off, get back on!”

Well, I am a living embodiment of that saying. No, literally, I have fallen off, been bucked off, dumped off, scraped off, rolled over on, and in every other way imaginable separated from my seat on that proverbial horse. And I have had to get back on.

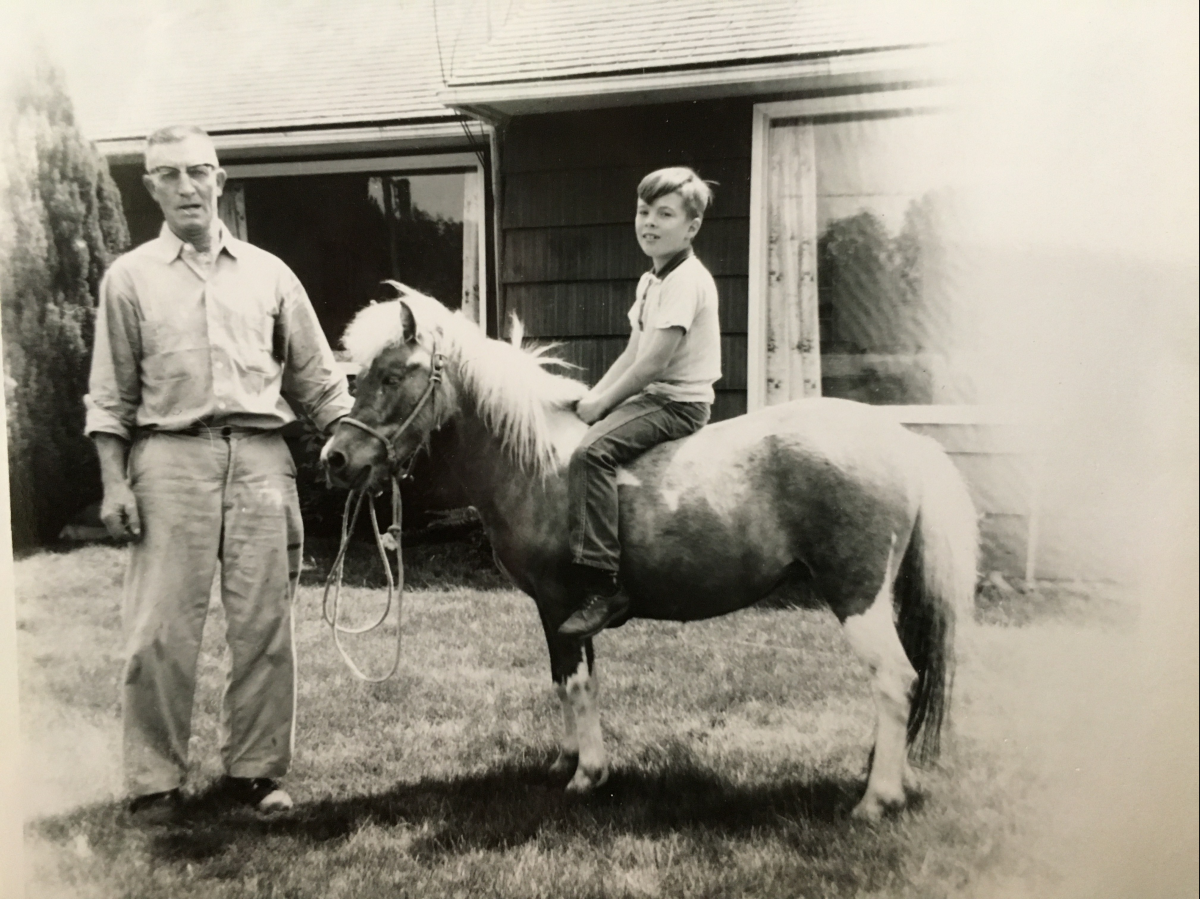

It actually started with ponies.

I can’t remember Granddads place without ponies. It seemed like there were always a bunch of them, mostly of the Shetland variety. An elderly neighbor lady once asked Granddad: “Lindsey, why do you keep so darn many ponies?”

“Why Mrs. Busby,” Granddad replied, “I keep those ponies so my neighbors have something to talk about!”

I don’t remember Mrs. Busby being overly impressed with that answer.

I think Granddad kept those ponies because they reminded him of the days when he farmed and logged with teams of draft horses like Barney and Luke, and Pat and Dan. In fact, with the help of a neighbor he built pony sized carts, buggies, wagons, and even a chariot for his Shetland teams to pull.

But of course, these were not just pulling ponies, they were riding ponies too, and it was my job and that of my sister Susan to ride the darn things. And that was often easier said than done.

Every horse needs a rider with the expertise and ability to guide its development as a saddle animal. This is especially true of Shetland ponies whose strength, endurance, durability, intelligence, and stubbornness per pound are unsurpassed. These ponies were developed as tough little beasts of burden in the Shetland Isles and those on the Ward place ran true to their genetic code.

The problem was, none of the adults in our family, with the rare exception of Dad, would lower themselves to sitting astride these critters long enough to impart any meaningful training or discipline. That left the job to Susan and me.

I think Susan would readily admit that her task was significantly easier than mine. She was assigned “Black Beauty”, a good-natured, well-mannered, pony with a black coat and white forehead star. I on the other hand was given “Cricket” to raise and train. Cricket looked nothing like a cricket–she had been named for a jet-black family pony from generations past, but was actually an attractive fawn and white mix of colors. As nice as she looked, she was tough as nails and not overly fond of children, particularly ones with the audacity to climb up onto her back. In fact it seemed like one of her life goals was to ensure that my tenure as her rider was a short as possible, every time I swung into the saddle.

Over time she proved extremely creative as to the form her efforts took to unseat me. Classic bucking was of course a favorite, but she also enjoyed rearing up on her hind legs. If I failed to slide out of the saddle while her nose was pointed skyward she would often throw herself over backward in an attempt pin me between the saddle and the ground. She came close to success a couple of times but eventually I learned that to keep a horse from rearing you gave it its head and squeezed forward with your heels. So, she moved on to what was for me the most terrifying tactic of all—the dreaded cherry tree scrape-off.

Granddads primary farm crop was tree fruit—sweet and tart cherries and Italian prunes. The farm, really, was one big orchard and the rows between the trees made a fine place to work a horse, except when that horse was an iron-jawed pony like Cricket.

Cricket seemed to know instinctively that unseating a rider was as simple as using good behavior to lull him or her into a relaxed state of being, then making a mad dash toward the nearest low hanging tree limb.

Most of the time I was quick enough to grab a rein and pull her away from the tree, or just throw myself to the side and miss the oncoming branch. On this particular day, though, she caught me full on in the chest with a thick cherry limb. Rather than lifting me up and off the horse for a quick trip to the ground, this limb pressed me down into the saddle bending me back and scraping across my upper torso, neck and head as Cricket continued her flight to freedom. Thankfully my boots came free of the stirrups and I fell to the ground after we cleared the tree.

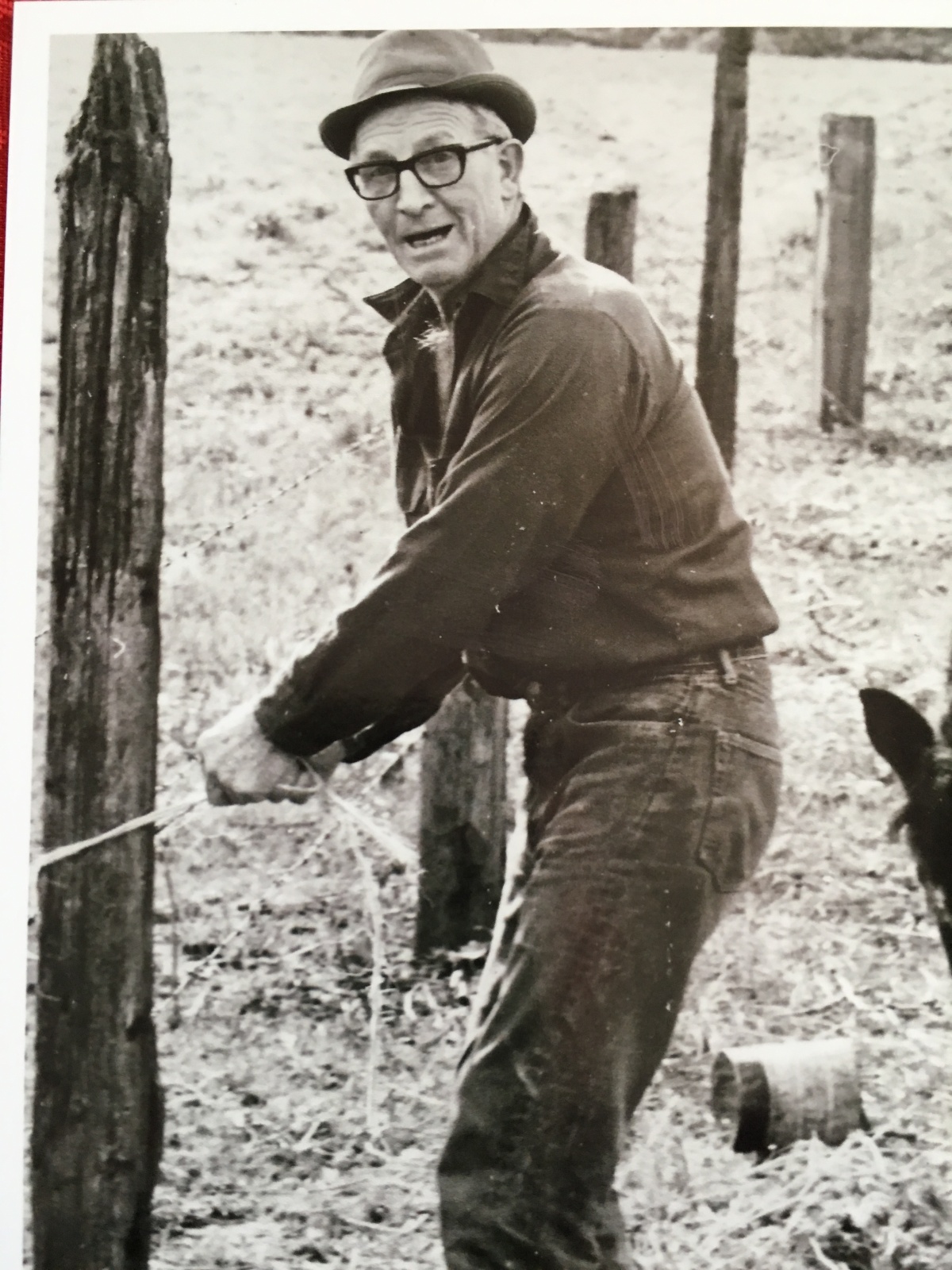

I’m not sure how long it was until Granddad found me. He was holding my horse by the reins and kneeling beside me as I lay stunned, in the soft dirt beneath the tree. My shirt was torn, and from chest to forehead were scrapes, cuts and bruises. My back hurt where it had been wrenched over the cantle of the saddle. Granddad helped me to my feet and gave me a quick once over looking for broken bones and other serious damage. Then he said sympathetically: “Son, we’re going to take you up to the house in a minute and let Granny fix you up, but before we do you’ve got to get back on this horse.”

I must have had a stricken expression on my face because he bent down, looked at me intently and said: “If you don’t get back on now you will have to fight this same battle with Cricket every time you ride her. You’ll be afraid of her and you’ll both know it.”

I nodded and turned to the pony. Granddad helped me into the saddle and handed me the reins. We made an uneventful circuit around the orchard; Cricket, evidently having had her fun for the day, was pretty cooperative. When we got back to where Granddad stood he took the reins and led the pony and I up to the back porch where Granny waited with a word of comfort, and bandages.

I’ve come off a lot of horses in the years since, both literally and metaphorically. For better or worse, I’ve always seemed to be able to climb back on.

I guess I can credit Cricket and Granddad for that.